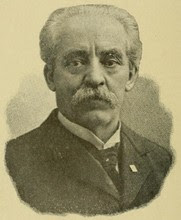

Moses Hull was born in Waldo, Ohio, one of seven children of Dr. James and Mary Hull. His family had long been part of the United Brethren Church, but when Moses was 16, he was introduced to the ministry of Ellen and James White, Seventh Day Adventists. He joined their church in 1857 and became a prominent minister and debater.

That did not keep Hull from investigating a new belief spreading across the country, Spiritualism. During that time, he met many “true and earnest mediums,” according to his son Daniel. Moses tried to leave the Whites’ church, but they convinced him to stay.

According to Assis, “Although he confessed his error and remained in the Adventist ministry for a time, he was never the same man. He preached his last sermon as an Adventist on September 20, 1863, and then became a leader in the ranks of spiritualism.” To this day, Moses Hull is held up as an example of one who was tempted by Satan and the evils of Spiritualism. Ellen White wrote, “There are few who have any just conception of the deceptive power of spiritualism and the danger of coming under its influence. . . .”

Ironically, Hull brought the Bible to Spiritualism. He taught scriptures from a Spiritualist’s view and published two volumes, entitled “The Encyclopedia of Biblical Spiritualism.” He saw spirit communication as a culmination of Christianity. “If the Bible was accepted, Spiritualism must be accepted,” he said.

Hull became known for a series of debates with ministers. Some of those debates are recorded as historical documents, including the Jamieson-Hull and Hull-Covert Debates. He also published numerous books, articles and newspapers.

Moses Hull spent forty-five years promoting the cause of Spiritualism. “He was ‘called to preach’ not as a mere mercantile business, but because the world needed his message, needed enlightenment, and the business of obtaining a livelihood was secondary and incidental to that higher purpose,” his son wrote.

That did not keep Hull from scandal. In 1873, he and wife, Elvira, divorced on amicable grounds. She remarried. Moses and long-time associate and Spiritualist, Mattie E. Sawyer, drew up a common law contract with each other. The event gave Seventh Day Adventists more fodder to condemn him and even some Spiritualists were put off by the circumstances. He was even arrested at one point, but the case was dismissed.

The scandal did not last. Hull became interested in creating Spiritualist education centers. Plans were drawn up for The Training School. The instructors were Professor Andrew J. Weaver, Alfaretta Jahnke (Moses’ youngest daughter), D.M. King, and Moses and Mattie Hull. The school succeeded for a few years before it closed.

Fortunately, Hull’s failure was being watched by a man in Whitewater, Wisconsin, Morris Pratt. The Morris Pratt Institute became a corporation in 1901. The school was managed by nine trustees and Moses Hull became the President.

Hull was also politically active. He supported the women’s rights movement and the Equal Rights Party in 1872. Later, he became a national leader of Greenback-Labor Party and tried to secure more rights for farmers, workers and women. He ran for Congress on the Socialist Party ticket. His political ambitions ended abruptly when Moses Hull passed to the Spirit World in January 1907.

Additional reading:

Assis, Luis Gustavo S. “A Pastor, A King, and a Necromancer: Lessons from the Forbidden Ground of Spiritualism.” In Ministry, December 2011.

Hull, Daniel (1907) Moses Hull. Maugus Printing Company, Wellesley, Mass.

Excelentes artículos, que nos enseñan sobre las personalidades que han mostrado al mundo las bendiciones del Espiritualismo.

Muchas Bendiciones.

Víctor de Anda

Cd. de México

Translation

Excellent articles, which teach us about the personalities that have shown the world the blessings of Spiritualism.